A blog developing a corpus of short films, originally in conjunction with Professor Jeffrey Middents' course Literature 346/646, "Short Films," at American University during Summer 2006, Fall 2008 and Fall 2011.

Monday, June 19, 2006

"Fait D'Hiver," Belgium

Director: Dirk Belien

Writer: Johan Verschueren

Country: Belgium

Language: Dutch

Year of production: 2001

Length: 7 minutes

Source: DVD 878 (nominee, 2003 75th annual Academy Awards for short film)

The payoff of this short film is huge, saturated as it is in its half-dozen minutes with sensational events set off by a trajectory that moves quickly from the mundane to the incredible. Events along this trajectory prove to be a progressive complication of the protagonist’s problems and a macabre, but somehow humorous, lesson in contrasts: By the end of “Fait d’Hiver” gridlock doesn’t seem so very unbearable.

The first scene opens with an appropriate but banal contrast of a snow-covered car and Beach Boys music, the one flouting the other. The music comes from the driver’s radio, which, once the camera cuts from an exterior shot of the car, wipers working, to an interior shot, updates the driver on the traffic situation. The update of the obvious only heightens the driver’s agitation, and he curses, and curses at the driver behind him who urges him with his horn to inch forward into the space that’s just opened up, and curses at the emergency vehicle that blares by in a flash of blue. This frustration and the driver’s popping of pills take up the first two minutes of the film and set the point of reference for the escalation of the protagonist’s problems from quotidian to incredible.

To remedy his boredom the driver grabs his cell phone from a newly opened package to test it. The camera cuts to a shot of a telephone sitting atop a chest of drawers. From behind the chest rises a little girl in response to the ring of the telephone. She hugs her doll and looks shyly at the phone, which induces her on the third ring to answer. “Hey, honey, it’s Daddy,” says the driver, and the relationship is set between the only two speaking actors in the film. A smile spreads across the girl’s face, and she moves to put her doll in its stroller as her father asks, “Is Mommy there?” Before she can answer the question the phone, which the six-year-old has been unknowingly pulling toward the edge of the chest of drawers, crashes to the floor, as if to signal the upcoming domestic crisis.

The driver, concerned from the noise of the phone’s fall, repeats his question in the flustered tone he’s used to curse gridlock. “Mommy’s upstairs in the bedroom with Uncle Wim,” she says. Cut to the driver’s gaping mouth which, in incredulity, turns into a stuttered laugh and then into the work of forming the words, “Uncle Wim? But we don’t have an Uncle Wim, sweetie.” The little girl confirms Uncle Wim’s existence and the fact that he is upstairs with Mommy. The driver’s shocked silence prompts the little girl to query, “Daddy?” The camera cuts to an extreme close-up of the driver’s mouth, just open as if preparing for breath to return. Instead of a breath, a gulp, and a favor: “Honey, I want you to do something for me . . .”

The little girl listens, and we see her listen though we hear nothing except, after a pause and a slow dolly back, “Yes, Daddy,” then she sets the phone on the table and starts her ascent of the stairs. Her steps are deliberate, even difficult, without hurry or alarm. This carriage will characterize the little girl throughout the remainder of the film, despite events, and will set the incredibility of the events in contrast to the calm of the girl’s reportage. Alarm and agitation we get from the driver, the adult, who ostensibly understands the weight of his daughter’s innocent report. He looks far into the distance, unaware of the traffic jam; he pops more pills; he rubs his head. His curse in response to more honking is half-hearted, perfunctory. The camera cuts from a shot of the concerned driver to another shot of the concerned driver to mark the passage of time.

Time has passed. We are about to find out how much. The next shot shows the little girl clumping down the last of the stairs, unhurried. She picks up the phone. The angle of the camera has not changed on either of these actors. Their individual expressions have also remained constant: his concern, her oblivion. “What happened,” the driver rushes to ask as soon as the little girl says, “Hello, Daddy.” Cut to a dolly toward the bedroom door. The little girl’s conversation with the driver is overlaid and the motion of the frames is slowed, perhaps to signal events that have already occurred, perhaps to underscore the drama. The first hint—and it is only a hint—of nondiegetic music drones in at a bass range of whole notes that match the slowed motion. “I went upstairs to the bedroom,” she begins, and the camera shows her leaning her ear into the door. Over her explanation comes the gasps and soprano of sexual climax. “. . . and knocked on the door like you asked me to.” The camera speed has not actually slowed, but instead has mirrored the little girl’s measured approach of the bedroom door. “Mommy,” she says after knocking. “I heard Daddy’s car. He’s home.”

Truncated orgasm follows this announcement and the door flies open to expose a naked woman holding an orange towel. As the little girl continues her retelling of the story the camera does slow to show a flustered woman look at her daughter and move past her into a room down the hall. The little girl reports the scene: “She came out of the bedroom, all naked.” And after the husband pushes her for more information (“And? And?”) a slow-motion shot of Uncle Wim rushing to put his blubber back under the cover of clothes comes into both our view and the girl’s view. She looks on unperturbed until she hears her mother’s scream and the thud of her body. Her figure struggles in slow motion to run toward the sound while her voice in the present calmly tells her father the story: “And she ran into the bathroom and fell on the floor.” Nondiegetic tympanis prepare the viewer for a dolly up to the image of a naked woman supine upon the bathroom tile. Her eyes are shock-open, unblinking. A stream of blood exits her mouth. The little girl kneels and looks upon her mother with nothing if not pity, and twirls a lock of her hair, as if in consolation if not understanding..

“And I think she’s dead,” says the little girl first about her mother and then, with a pronoun change, about Uncle Wim, who’s shock at the sight of the little girl next to her lifeless mother sends him careening out the second floor window and, spread eagle, into the swimming pool below, touched by a blanketing of big snowflakes in the leisure of fairy-tale falling. “Swimming pool? What swimming pool,” says the driver, whose look of agitation turns to one of horrified disbelief when he checks the number that he dialed with his new cell phone. “Holy shit.”

Cut to black, cue little girl’s voiceover: “Daddy?” Roll music for the credits: “You gave me the wrong telephone number . . .”

By mixing elements of the sensational (wife’s infidelity, husband’s coincidental phone call home, mother’s fall) with elements of the incredible (little girl’s calm retelling of events, Mother’s and Uncle’s unexpected deaths, the banal misdialing that starts it all off) the director has managed not only to provide a little perspective on life’s little problems but also to create a textbook perfect short film without the aid of the technical cutting edge (a la the animated winner, “The ChubbChubbs”) or overdetermined narrative development (cf. the winner of the live action short). In seven short minutes the director sets up the pattern of contrasts that leads to the shocking twist, while managing to keep the twist shocking by making it mundane. The “reveal” is big and satisfying because it takes the viewer simultaneously toward the climax of the incredible and back to the quotidian, while contrasting the protagonist’s (and our own) shock at the unquantifiable prospects of his misdialing with his relative relief that he in fact misdialed.

Venice Beach

VENICE BEACH

VENICE BEACHDirector: Jung-Ho Kim, South Korea, 2003 4:30min

Source: www.atomfilms.com

The film opens in a workout room that we quickly realize is for crabs only. Even though a small twig dumbbell is in focus in the front of the frame, our attention shifts to a crab emerging from the shadows in the back of stage left ready to workout. The shot opens up to reveal another crab on a punching bag and the first crab now running on a red treadmill. A third crab scurries in and surveys the room and goes over near the punching bag and starts imitating the crab's punching movements. Here we find a recurring theme of imitation and adoration and the next three minutes of the film this crab tries to fit in despite being a newcomer. His biggest challenge is trying to keep up the pace on the treadmill, which he attempts after the first crab by imitating his movements as he runs on the treadmill. However, just when you think the story is about Crab #3, a fourth crab enters and he too is out of place and awkwardly tries his luck at the treadmill. Soon he masters a good treadmill technique and leaves Crabs 2 and 3 in awe who then imitate him by emulating his successful treadmill technique.

Not surprisingly, yet interesting to note, is how cinematic this animated short is. The computer animator has captured great detail including the tile mosaic on the floor and every bump on the crab's claws. In addition, there is a variety of camera shots including the standard closeup and reaction shots featuring eyeline matches. Though this is an animation and the non-diegetic music is light-hearted, the film is still serious in tone. This could be my own interpretation due to the lighting. Each frame is dimly lit; only the focused objects (crab, treadmill, etc.) are bright and lit. Everything else is in shadows. This short features many dark browns and tans and shadows which add to a very non-Disney feel, which is in contrast to what is expected of animation. Because of this the gym appears ominous and threatening initially. This, to me, is very interesting; however, I am not sure if this is indicative of Asian animation. This short film won the Digital Art Award at the Grand Prix in Tokyo and I believe it was well-deserved. What really impressed me were the details! This appears to be a calling card film, I could see these characters being used again and their stories expanded upon. This short is humorous, cute, and yet at the same time, has serious undertones reflecting human behavior and the need to keep up with the "Joneses."

O Branco, Brazil

O Branco (The Color White)

O Branco (The Color White)Directed by: Angela Pires, Liliana Sulzbach, Brazil, 2000, 22 mins.

Source: www.atomfilms.com/af/content/o_branco

The film opens with a shot of a burning sun. The shadowed figures of a man and boy walk through a field while a guitar plays in the background.The son asks, “Daddy, what color is the sun?” to which the father replies, “It depends on the hour.” He takes Fredi’s hand and traces a big circle in the air, explaining that the sun changes color during the day. Fredi says, “I prefer it white,” before adding, “I don’t like it when it gets dark” as his father places a stone in his hand. As they throw rocks towards the sun, his father says he understands this fear and replies, “It’s symbolic.” He then describes symbolism. They hug as Fredi’s father explains,“When I hug you really tight, which means I will be with you forever.”

Suddenly the sky darkens and we cut to an older Fredi getting dressed in a white bathroom. A narrator’s voice informs us that it is Saturday and that Fredi, who lives with his seamstress mother, always knows the days by “color.” Fredi is blind and spends almost all of his time inside, with the exception of trips to the market and Saturday afternoons at a park.

This Saturday, his mother leaves him on a park bench while she makes a phone call to “

Back at home, life is the same. Fredi continues his lonely routine and somber music plays as scenes virtually identical to the earlier weekday scenes fade into one another.

The next Saturday Caludia brings Fredi to swings on the river-side of the park and asks, “If you could see, what would you want to see the most?” He replies, “Branco” and explains, “It’s symbolic.” Fredi’s mother is angry when she finds him and drags him away.

On the following Saturday, Fredi adds a spray of cologne to his dressing routine, but is dismayed when his mother informs him, “No park for some time.” It is unclear whether this is because of some falling out with “

I was interested in this movie because it won a slew of awards including: Best Short Film, Rio de Janeiro International Film Festival 2000; Best Latin American and Caribbean Film -

Die Zwoelfte Stunde(Eine Nacht des Grauens) (The Twelfth Hour or Night of Horror)

Keri Collins

Wales, 2004, 7:00

http://www.bbc.co.uk/dna/filmnetwork/A3743804

Despite the title, Die Zwoelfte Stunde is actually a British film. It begins as a typical black and white silent film reminiscent of the early years of film making. Raymond is an adolescent boy who has made up his mind, despite warnings, to go to the haunted castle and confront whatever he may find there. It is soon evident that this is not your ordinary silent film, but rather a twist on a classic form done completely with British humor. The dialogue screen goes back and forth between Raymond and one of the towns people arguing whether or not there exists true evil in castle. Raymond's repeated argument is "Not!"

Finally Raymond sets off for the castle only to be immediately confronted by a creepy vampire with extremely long fingers who stalks down the hall in true horror-movie fashion. When Raymond confronts him, the vampire, Nosferatu, offers Raymond a cup of tea. The dialogue screen tells us that Nosferatu is adding poison to... poison him, but Nosferatu is upset when Raymond asks for milk in his tea, and the poison is not imbibed.

Cut to the angry villagers who declare that they must save Raymond by killing the vampire! One villager points out that perhaps they could resolve the argument peacefully, there's a moment of contemplation, followed by shouts of "Kill him!"

Nosferatu shows Raymond out of the castle since it's getting dark and he'll be going out soon. When they leave, the angry villagers run up the hill and stab at Nosferatu with pitchforks and other agrarian tools, except to no avail, since Nosferatu creeps out of the pile and makes himself disappear. The villagers think they have saved the day and retreat back down to the village. Raymond shrugs, somewhat satisfied with his day.

I chose this film because of how typical the humor is to the dry British humor that is so well known. There was definitely a Monty Python feel to this short and I found myself laughing out loud, despite the fact that I was watching a b/w silent film.

Collins plays with the form and uses it in the comedy. It's unexpected and quite funny to have the boy and the older man arguing back and forth on dialogue screens and what they're saying is very much modern language. Also, there is a part when Raymond asks Nosferatu a question and Nosferatu is seen giving a long and quite animated response, only to have the dialogue screen pop up with "Na." I also felt the play on the "angry villagers" was incredibly funny, especially when the on man asks if they can resolve things peacefully--hysterical!

Also in the form of silent films is the music--it's reminiscent of the music we heard in the silent film we watched the first week of class. The music follows the action and adds to the mood, also indicates urgency, stunts, etc, very well.

Collins is also playing on horror films, both with the title and the stereotypical vampire. When Nosferatu and Raymond are leaving the castle, Nosferatu is still wiggling his super-long fingers behind Raymond. When Raymond turns around, Nosferatu apologizes and says it was a force of habit. Nosferatu is also noted as being born from Hell, also son of colon and Janet Davis--hysterical!

The self-relexiveness of the film was what really drew me in, Collins made fun of both the silent film and the horror film but creating a silent horror film. He used all of the aspects attributed to both films, right down to the shadows of the castle, the innocent insistence of the boy, and the thematic styles. The comedy isn't just found in jokes, but rather it's embedded in the way the film is made.

DECALOGUE, SIX

The Decalogue, Part Six, Directed by

Source: The Decalogue [DVD 86]

At the café, she asks why Tomek loves her. He says he doesn’t know, but it isn’t a sexual thing, as he no longer even masturbates while looking at her. She learns that he lives with an older woman whose own son is abroad. She asks him to hold her hand, but he trembles as he does so. They go back to her apartment, where she changes and asks him if he has been with a women before; he says no. She straddles across from him, tells him that she is wet and that means she is aroused. She slowly brings his hands closer to her body, up her legs – but before he gets his hands all the way up, he comes in his pants. She says, “Already?” He nods. She replies, coldly, “That’s what love is. Go wash up.” He runs away.

The film plays on many standard conventions of love and love stories, while tweaking them in inventful and jarring ways. The shift in perspective has a clear effect on the viewer as, by the end, Tomek’s last comment is as much of a sucker-punch as her comment had been to him earlier. There are certain Polish elements that make this work – most notably, the presence of Soviet-bloc era apartment complexes which exist all over

Wade's Picc Mi (Little Bird)

PICC MI (Little Bird)

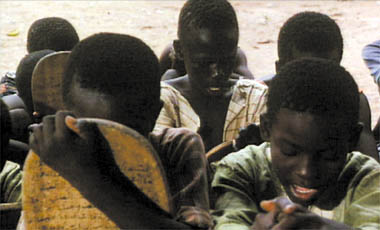

Directed by Mansour Sora Wade, Senegal, 1992, 16 minutes

Source: Three Tales From Senegal (VHS 4339)

In a Senegalese village, a group of destitute children are gathered in the dirt around a seated priest, reading prayers from their tablets as the priest eats greedily from a bowl of food. One of the children, Madou, eyes the priest suspiciously, and turns his gaze to a bird’s nest perched in a tree above. The priest instructs the children, “Go and beg,” and they disperse. Madou wanders the village with a collection cup, asking for “Charity in the name of God.” One kind woman in the village offers him food. Madou next ventures to the marketplace, where a woman pays him to carry her groceries to her car. As Madou is looking in a storefront window, an apparently handicapped boy, who wears rags and pushes himself along while kneeling on a skateboard, rolls up to the curb and asks Madou for help crossing the street. After Madou has pushed him across, the boy stands up, exposing the artifice of his begging ploy (i.e., he’s not really crippled), and laughs at Madou. He introduces himself as Ablaye and the two boys make fast friends, wandering around together. As they pass a gated establishment – what looks to be a school – a boy in regal attire sits inside the gate, casually chewing food. Madou and Ablaye make eye contact with the boy, before continuing on their way. Next, they play a trick by filling a wallet with money and placing it in a suited man’s path. As the man reaches for the wallet, the boys cry out, “Thief! Thief!,” startling the man into leaving the wallet and moving on. In another scene, the boys watch from a distance as a birdseller sells a man one of his caged birds. Later, the boys exchange their respective stories: Ablaye’s father has lost his herd during a drought, while Madou’s mother has given him to a priest, for whom he must spend his days begging. Ablaye leads Madou to the garbage dump where he and his father live, and gives his father the money he has earned that day from begging. His father gives him permission to “go and play.” As the two boys walk off into the distance, Madou asks Ablaye if they will meet again tomorrow. “Maybe,” Ablaye replies. Madou walks home at night, in the rain. On his homecoming, he gives the priest the money he has earned. He lies down to sleep in the dirt beside the other destitute children. On closing his eyes, he has a dream that he is running freely along a beachfront. He stops at the edge of the shore, kneels, and holds out his arms to fly like a bird. He is replaced by the image of a bird flying upward toward the sky. End short.

While this is the “surface” narrative of the short, a second, metaphorical narrative is simultaneously told through the short’s innovative soundtrack. Madou’s sporadic voiceover narration is coupled with narrative lyrics sung by a child’s choir, to present the tale of a bird whose mother has left him alone in the nest, while a crocodile lies in wait down below. The crocodile lies to the bird and tells him that his mother will soon return, in an attempt to lure the bird down from the nest. The bird, however, knows the crocodile is a lying predator, and also knows his mother is not coming back.

Reading this analogy into the world of the film, the bird is representative of Madou, Ablaye, and the other fragile, motherless children who must make their own way in a world filled with predatory crocodiles – the adults (or, more specifically, adult males, since the females in the film are those who provide temporary, “surrogate mother” aid to the impoverished children), such as the priest, who, instead of offering protection, shelter, and sustenance, exploit the children for the sympathies of society, forcing them into a worldly wisdom beyond their years. The secondary narrative of the soundtrack intersects in moving ways with the primary narrative at opportune points. For instance, after Madou and Ablaye’s brief encounter with the boy they could have been – the well cared-for boy beyond the schoolyard gate – the child’s choir sings, “Mother help me! Oh! Mother. Help.” Similarly, as Madou lies down in the dirt at the end of the day, closing his eyes before his dream, the child’s choir sings, “Mother come and get me,” suggesting a desperate plea for escape, cried in vain. Later, there is direct dialoguic reference to the bird-crocodile symbology. After a stick-wielding street vendor chases Madou and Ablaye away from his premises simply because they are playing, Ablaye advises Madou: “The crocodiles are everywhere. Don’t let them eat you.”

To further the bird-crocodile symbology, there is bird imagery planted throughout the film. For instance, there is a beautiful composition as Madou first enters the marketplace, where we see him backgrounded against various cages of birds. The bird-seller scene is also quite striking. As the bird-seller reaches into his cage to pull out a bird for the customer, the first bird he pulls out is dead; he gives it no regard, throwing it onto the dirt, as we cut to Madou and Ablaye’s petrified reaction. (Another striking detail of this scene: Madou peers from behind a yellow sheet hanging on a line, while Ablaye, from a red sheet, to Madou’s right, thereby forming the rightmost two colors of the Senegalese flag.) There are also seemingly non-diagetic chirping bird sounds added to the soundtrack in various places, as when Ablaye and Madou exit the marketplace to venture into the desolate territory where Ablaye lives amidst disposable waste. The execution of this animal symbology is masterful throughout, culminating in the final, haunting image of Madou stretching his arms out like a bird by the shoreline.

What is distinctly non-American about this short are obviously the settings (a Senegalese village and marketplace), dress (robes, bare feet), and customs (eating without utensils, for instance) on display. On a more narrative level, the incorporation of the secondary, fable-like storyline, is distinct. The use of (especially animal-based) fable is an ancient African narrative tradition that is here synthesized and modernized, resulting in a hybrid narrative form where the secondary and primary storylines talk to one other and add to each other’s punch. The film has an agenda, advancing the cause of impoverished, exploited children in Senegal, but its reliance on metaphor allows it to avoid heavy-handedness, and instead present its subject matter in a subtle, affecting way. All in all, this will probably turn out to be one of my favorite shorts that I’ve seen. The kinship between the two boys is endearing, the film’s narrative structure is exquisite and complex, and its sequences are carefully composed and expertly shot. In sum, this is one of those short films that truly flies.

Sunday, June 18, 2006

A Alma do Negocio (The Soul of Business)

A ALMA DO NEGOCIO (THE SOUL OF BUSINESS)

Directed by Jose Roberto Torero, Brazil, 1996, 8 minutes

Source: hurluberu films (pause and skip the trailer)

A soothing musical score starts as a married couple are waking up and begin to advertise about everything they use to each other, the bed sheets, the shower, the towel, the coffee, the milk, etc. But when the wife cuts her husbands finger, she advertises about the knife. Then the husband advertises about the silverware and stabs the wife in the hand. The wife then advertises about the dishes and smashes it on the husband's head. Then the husband advertises about the meatmincer and.........yep, sticks the wife's fingers in them. Then the wife advertises about the skewer and stabs the husband in the chest. Then the husband advertises about the handheld blender and stabs it into the wife's chest. Then the wife advertises about the drill and drills the husband in the chest. Then the husband advertises about the new chainsaw and makes a huge cut on the wife's neck. Then the husband collapses on the chair as they are both dead, and then avoiceoverr advertises about band-aid.

This short film is supposed to be a graphic horror film but because the couple are speaking in the same uplifting commercial voice and trying to retain that fake smile while dying, it made me laugh when they were cutting each other up. I really enjoyed this film because with everything so perfect, so white, something this horrifying was bound to happen. This film was making a mock-up of the commercials with products that seem American, like the Michigan mix blender, the White&Becker drill, and Joe's Coffee. They don't actually look at the fourth wall to advertise but they do have an eyeline match to show that they are talking to each other. Quite a satire of American life with the couple being surrounded by name-brand products.

I chose this film because I thought it would be interesting to see what a horror film is like internationally. By watching this film I saw that graphic violence is more explicit. I saw long look at cut up fingers, at a wounded chest, and the full carnage of a chainsaw. Also I am intrigued by people like Jose Roberto Torero who not only directed this short but wrote it as well. JRT has directed and written many shorts but also made feature films like Pele Forever in 2004. Truly this film is very entertaining if not scary.